In Flora Tristan’s “The Workers’ Union,” an appeal to emotion is made to frustrate the workers in recalling how little progress has been made in the quarter of a century prior to the publication of this work in taking care of the European, in particular the French, working class. As we’ve discussed in class, one of the most major issues with these types of writing, like Engels’ call for action for example, is that they seem to believe that the working class can both afford the time to improve their livelihood and have the education needed to understand how they can bring about meaningful change/reform. Tristan’s call differs in this regard because she acknowledges that just the publication of her work will not be enough. Specifically, she states on page 192 that,

“I understand that, my book published, I have another work to accomplish, which is to go myself, proposal for union in hand, from city to city, from one end of France to another, to speak to the workers who do not know how to read and to those who haven’t the time to read. I tell myself that the moment has come to act. And for those who really love the workers, who want to devote themselves, body and soul, to their cause, a wonderful mission there is to fulfil.”

We can see through this quote that her piece is intended just as much for those urging reform as the working class itself, saying that just lecturing from a distance is not enough. There needs to be a sense of responsibility, of teaching, to spread beneficial ideals that will make society a better place. If people are unwilling to do this, it isn’t doing that much to improve conditions as her critique of the last two decades shows.

This compounds upon her earlier request for coordination. She advocates for a sort of union organization with dues to be paid so that money can be used to bring about change by applying pressure to the government and if necessary help look after individuals who are older, injured, or at some sort of risk due to their economic predicament which the then-current system facilitated. She compares such a system to the the Hotel des Invalides, a sort of government-run care facility for retired French servicemen, and puts forward an idea of paying into retirement care down the road in a way that sounds very familiar to the concept of U.S. Social Security. In this way she not only says that the working class needs more direct coordination from leaders who champion reform, but the movement itself needs to get behind a concerted effort to solve problems on its own if nobody else is willing to step up to the plate.

In a way, Tristan is taking a more hands-on approach. There are many parallels to various progressive movements in American and European history, but if I had to make one, it would be that if Engels is to working class reform what Harriet Beecher-Stowe was to American abolitionism, then Flora Tristan would be the movement’s equivalent to someone along the lines of a John Brown.

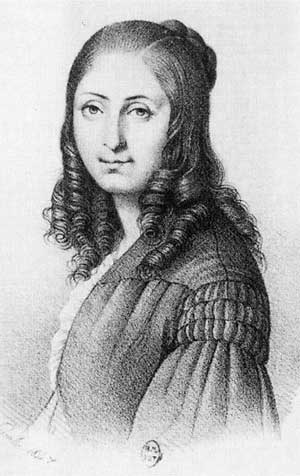

Tristan died only about a year after she published this book, our reading states, and was in poor health for much of that time. So the saddest part of this movement to me is how we never got to see exactly what effect her tour and travels would have had in bringing about change. What would this have looked like? Would sweeping reform had come sooner if she had lived? What leaders might have answered her call? Would she have gotten more radical over time? Would women have gotten more political power and leverage sooner than what was the case as we know it? It is certainly intriguing to think of the possibilities. Personally, I read her piece and I see a leader who has mapped out exactly what she wants to push for and thinks she knows exactly how she wants to make it happen.